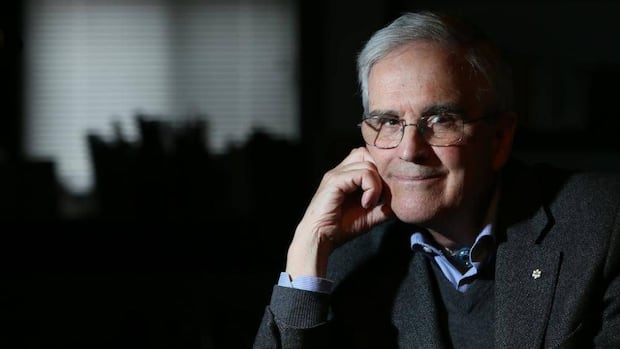

Dr. Balfour Mount, who coined the term "palliative care" and whose profound empathy helped revolutionize health-care in North America, died peacefully on Sept. 25 at the palliative care unit that bears his name.

He was 86.

Mount devoted his life to caring for others and alleviating suffering. In interviews, his family and colleagues remembered him as both deeply compassionate and as a fierce advocate for the humanity of those who are suffering.

"There's the legend, Dr. Balfour Mount, who's known worldwide," said James Mount, Balfour's son.

"But not much is known about the father he was, and the amazing presence he had, the love and the support. He wasn't just a friend or a dad. He was also my counsellor. I lost a lot."

Mount was born on April 14, 1939, in Ottawa. His father, Dr. Harry Telford Roy Mount, had served at both Vimy Ridge and Passchendaele during World War I before studying medicine and becoming Ottawa's first neurosurgeon.

"So the bar was set pretty high when Dad came along in 1939," James said.

Growing up, Mount struggled in school. He was a slow reader, James said. But he persevered with his studies and graduated from Queen's University with a medicine degree as a surgical urologist.

As a young man, he suffered a bout of testicular cancer, which, he told the Ottawa Citizen in a 2005 interview, forced him to confront his own mortality.

But it was after a church meeting to discuss On Death and Dying, a book written by Elisabeth Kubler-Ross that compiles the experiences of the dying, that Mount decided to shift the course of his life.

"It didn't occur to me that I didn't have a clue about death and dying," Mount told the Citizen. "I thought, 'I'm a doctor; I must know everything in the world about death and dying.' But, of course, I knew absolutely nothing."

The right approach

Inspired by the book, he led a small study into the experiences of terminally ill patients at the Royal Victoria Hospital in Montreal. The study, he said, demonstrated to him the "abysmal inadequacy" of care to alleviate both pain and suffering for dying people.

So, he travelled to England, where, under the tutelage of Dame Cicely Saunders , the founder of the world's modern first hospice, St. Christopher's, he saw first hand how pain could, in fact, be alleviated for terminally ill patients — with the right approach.

That approach included appropriate clinical care: opioids, for instance, had rarely, to that point, been prescribed in high enough doses to alleviate pain in terminally ill cancer patients.

But it also included a compassionate approach, an attempt to understand the root of a patient's suffering — to be present with them — as Mount often described it, according to colleagues.

He brought the approach back to North America and, in 1975, as part of a pilot project, created a hospital ward for the dying at the Royal Vic.

It was around that time that he coined the term "palliative care." He used the term in lieu of "hospice" because of Canada's francophone population. The term had a different meaning in French; it was an older word that referred, somewhat disparagingly, to a nursing home.

Mount shunned the limelight, though he earned numerous accolades and honours during his life. (City of Montreal)

John Scott, a longtime colleague of Mount's who helped him develop the first palliative care unit at the Royal Vic, said that, back then, physicians denied the existence of pain and suffering they didn't know what to do with.

Mount's approach, Scott said, went the other way.

"He was so articulate and so warm and personable at the same time as being brilliant," Scott said. "He was able to break through the denial and allow people to see that, actually, truth telling was relieving and healing."

'An extreme force'

Dr. Justin Sanders, the current Eric M. Flanders Chair in Palliative Medicine at McGill University, a position Mount once held, said in an interview that Mount was "willing to push hard against structures of care that he felt were insufficient."

"On the one hand, he was an extremely gentle and compassionate individual and on the other hand could be an extreme force," he said.

James recalled spending time with his father at the palliative care unit he founded. He witnessed his father caring for the sick and dying; he saw his fierce approach to understanding their suffering and providing comfort.

In his 60s, Mount was diagnosed with esophageal cancer, which required a permanent tracheostomy. He continued to work and to advocate for improved palliative care — he also became an early champion of whole person care — an approach to medicine that involves treating patients as "whole people rather than just a disease," according to Sanders.

Canadian stamps bearing the image of Dr. Balfour Mount, who died last Thursday in the palliative care unit that bears his name, are on display in Montreal on Tuesday, Sept. 30, 2025. Mount is recognized as the father of palliative care. (Christinne Muschi/The Canadian Press)

He also advocated against physician-assisted dying and for improved end-of-life care .

His work earned him many accolades, awards and honours, including as an officer in the Order of Canada, but he shunned the limelight and always said his greatest achievements were his children.

He was a devoted father, who applied the same principles of empathy and love that he gave to his patients in every aspect of his life.

The practice of presence

James recalled how his father had supported him through a difficult diagnosis of his own. Mount had accompanied him to the doctor's office when he received the news that he had a rare autoimmune disease. "I felt like the world had dropped out from under my feet," he said. "And I looked to dad and he smiled and said it's going to be OK. … and it was."

He kept that same composure in his final years and months as he grew more frail and tired beneath the burden of age and the esophageal cancer.

"He didn't wallow in self-pity," James said. "He always found a way to steer the conversation away from him and onto what he thought mattered and that was the person he was speaking with."

Before his death, he was admitted to the Balfour Mount Palliative Care Unit. There, family and friends kept him company.

Sanders sat with him and held his hand, occasionally saying a few words, but mainly doing what Mount had himself taught about palliative care, that it is the "practice of presence."

"This was an individual with extraordinary presence, and I think it was through his own presence, his own ideas, that he really inspired so many doctors to follow in his footsteps," Sanders said.

For James, the manner of his father's passing, without pain, in the unit he founded, was a gift — a final act of love.

"I don't want people just to remember him as the maverick that he was," he said. "I want them to know about the humanity of that. And I want them to know about the father he was and the gift that he was to all of us."

[SRC] https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/balfour-mount-death-palliative-care-1.7648430

Visit the website

Visit the website